Alphonse Mucha: Graphic Designers You Should know About

Alphonse Mucha: Art Nouveau master whose ornamental posters, flowing lines, and symbolic illustrations blended beauty, spirituality, and national pride to shape modern visual design

Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939) didn’t invent Art Nouveau, but for most people, he is Art Nouveau. His lush, looping forms and ornamental lettering became the face of a movement, a style, and a city. From Parisian posters to pan-Slavic murals, Mucha turned art into both spectacle and statement. He believed that beauty was not a luxury, but a spiritual necessity.

Fast Facts

Date of Birth

July 24, 1860

Place of Birth

Ivančice, Moravia (now Czech Republic)

Education

Academy of Fine Arts, Munich; Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi, Paris

Known For

Art Nouveau posters, painting, illustration, decorative arts

Big Break

Poster for Gismonda starring Sarah Bernhardt, 1894

Design Philosophy

Art as a spiritual necessity; beauty connects the soul and culture

Style Keywords

Flowing lines, floral motifs, idealized female figures, ornamental, symbolic

Era

Fin-de-siècle, Art Nouveau, early 20th century

Affiliations

Sarah Bernhardt, Georges Fouquet, Art Nouveau movement

Died

July 14, 1939 — Prague, Czechoslovakia

Origins

Alphonse Mucha was born on July 24, 1860, in the Moravian town of Ivančice, then part of Austria and now in the Czech Republic. He grew up in a modest Catholic household shaped by spiritual life, religious music, and folk traditions. His father worked as a court usher, and his mother supported his early creativity.

Before he could walk, Mucha showed talent. His mother tied a pencil around his neck so he could draw while crawling. He sang in church choirs and played violin. These early experiences shaped his lasting connection to spiritual art.

After being rejected by the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, Mucha moved to Vienna around 1879 and worked painting theatrical scenery. He developed a strong sense of visual rhythm and dramatic storytelling. In 1881, a fire destroyed the company’s operations, and Mucha returned to Moravia. There, he met Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, who became his patron and supported his formal training.

With the Count’s help, Mucha entered the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in 1885. These early years of struggle, support, and discovery became the foundation of his lifelong artistic identity.

First Steps

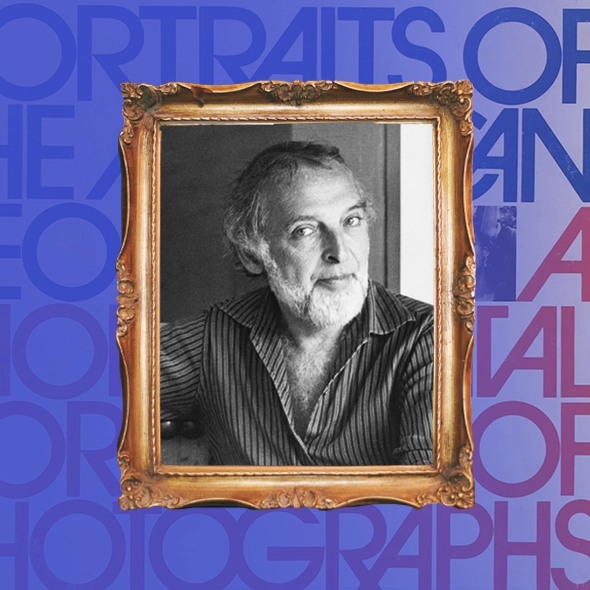

After completing his studies in Munich, Alphonse Mucha moved to Paris in 1887 to continue his artistic education and pursue work as an illustrator. He earned a living through magazine layouts and book illustrations, slowly building a reputation for graceful lines and decorative clarity. Life in Paris was often difficult. He lived in modest conditions and leaned on a small circle of fellow Czech expatriates for support.

During these years, he took on a wide range of commissions. Fashion plates, advertising materials, and theater programs all gave him space to explore symbolic detail and narrative charm. His distinctive approach to visual storytelling was already beginning to emerge.

Special Story:

When Gauguin Posed for Mucha

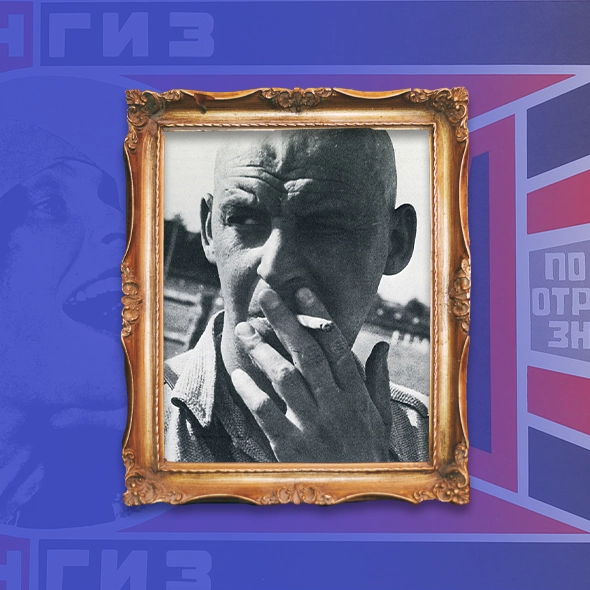

In 1893, Paul Gauguin, the famous French painter and sculptor, returned to Paris after his first extended stay in Tahiti. He brought back a series of works shaped by the island’s culture and landscape. His journey to Tahiti had been driven by a desire to escape European society and find new creative inspiration, but financial pressures forced his return.

At that time, Alphonse Mucha was living in modest quarters above a small restaurant on rue de la Grande-Chaumière, across from the Académie Julian, where he was enrolled as a student. The restaurant was a known gathering place for artists, and it was there that Mucha and Gauguin first met. According to biographical sources, Mucha offered Gauguin the use of his studio to help him prepare an exhibition of his Tahitian works.

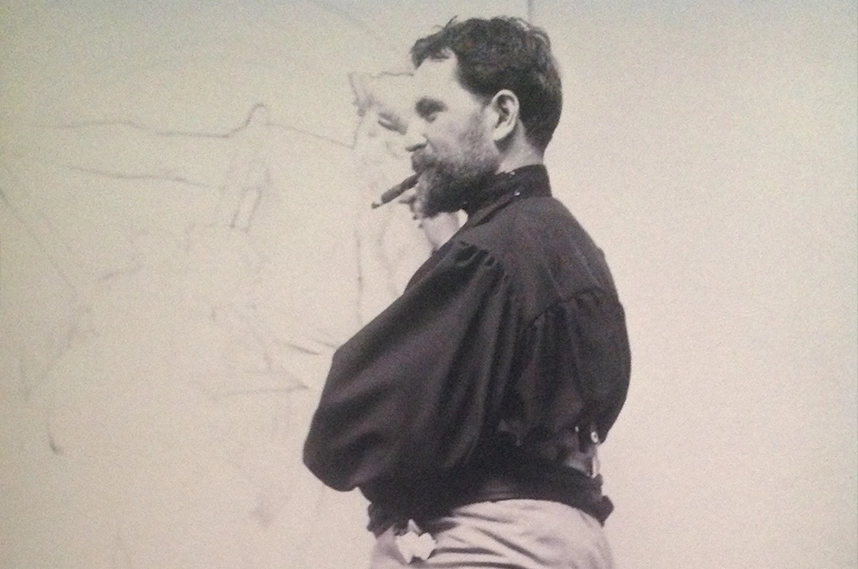

Gauguin also posed for Mucha during this period. Mucha, who often could not afford to hire professional models, frequently turned to fellow artists and friends. Their short-lived connection reflects the spirit of collaboration and mutual support that defined the Paris art scene of the 1890s.

The Breakthrough

On Christmas Eve 1894, Mucha was at Lemercier’s print shop when he overheard that Sarah Bernhardt urgently needed a poster for her new play, Gismonda. The regular artists were unavailable due to the holidays, so Mucha, then working on a different project, volunteered. He completed the poster in about two weeks, delivering a design unlike anything Paris had seen.

The poster appeared across the city in January 1895. Its tall, narrow format, delicate pastel tones, and ornamental detail captivated Parisians. Admirers even removed copies from walls to keep for themselves.

Gismonda’s success brought Mucha a six-year contract with Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress of the day. He became her preferred designer for stage posters, costumes, and sets. Each new poster added to his popularity. The French press began calling his style “le style Mucha.” Imitators emerged quickly.

"To Mucha, the purpose of art was clear: to communicate a spiritual message."

Rise and Recognition

Mucha’s fame after Gismonda spread beyond Paris. Between 1897 and 1900, Mucha held exhibitions in Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Munich, London, and New York. His distinctive line work and symbolic elegance appeared not only in posters but also on packaging, jewelry, furnishings, and calendars.

In 1900, he contributed major decorative panels to the Paris Exposition Universelle and was invited to join the jury for the graphic arts section. That same year, he began a new collaboration with jeweler Georges Fouquet, designing both shop interiors and original pieces in a style that combined luxury with Slavic motifs.

Although many saw him as the leading figure of Art Nouveau, Mucha resisted the label. He viewed art as a spiritual mission, not just decoration. His next steps would move away from commercial fame and toward deeper cultural ambitions.

Style & Philosophy

Mucha’s signature approach was rooted in clarity, harmony, and symbolism. His works combined clean outlines and soft pastels with an undercurrent of spiritual belief. While many associate him with the commercial Art Nouveau look of the 1890s, Mucha’s intent was always more personal and elevated. For Mucha, art existed primarily to communicate a spiritual message.

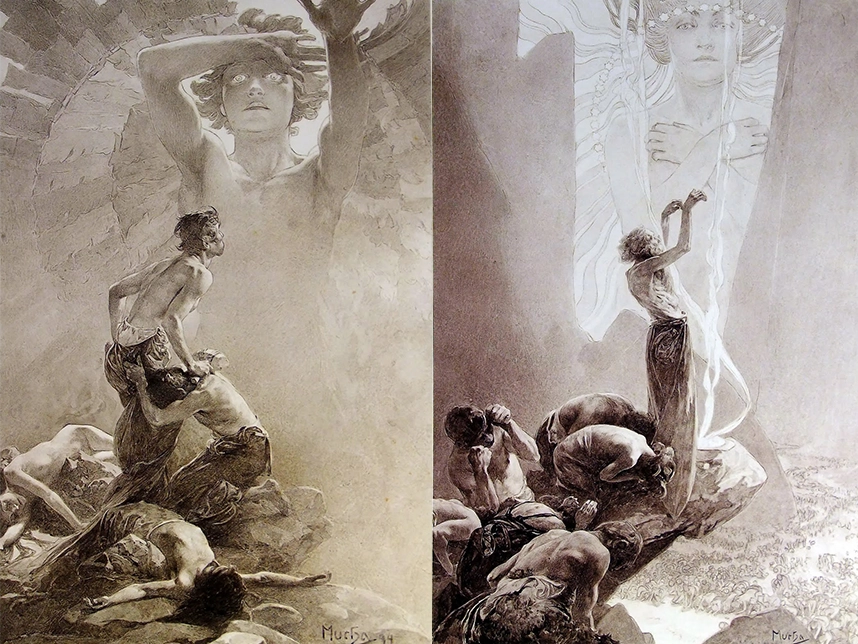

Even in his earliest symbolic work, Le Pater (1899), which was deeply mystical interpretation of the Lord’s Prayer, Mucha explored themes of divine justice and inner vision through allegory and ornament. He considered it his printed masterpiece.

In commercial settings, Mucha’s philosophy translated into visual generosity. He believed art should be accessible and uplifting. His women, flowers, and decorative patterns weren’t mere decoration; they represented an idealized, morally beautiful world.

After achieving fame in Paris, Mucha spent years (1904–1910) in the United States. These trips exposed him to a more modern, pragmatic audience and offered patronage for larger projects. Though less discussed today, this period served as a turning point, allowing him to pivot from commercial work to national and spiritual themes.

Mucha’s final phase of work was dedicated to the Slav Epic (1910–1928). This massive 20-painting cycle celebrates Slavic history and unity. While not graphic design, the work’s visual logic and theatrical compositions still echo Mucha’s poster sensibilities. He self-funded much of the project. Mucha saw it as his life’s true purpose.

Mucha’s last years were spent under increasing political tension. He was briefly arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo after the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia. Weakened and ill, he died shortly after in 1939. Yet even in these final moments, his art remained an act of quiet resistance.

Page 3 from Le Pater, 1899, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.

Defining Designs

The following works represent key moments in Alphonse Mucha’s design career. These are some of the designs that shaped his voice and helped define the Art Nouveau era.

Gismonda (1894)

The poster that started it all. A radical departure from Paris norms; tall, serene, and spiritually luminous.

Job Cigarettes (1896)

Voluptuous and hypnotic, with smoke and hair forming a single ornamental gesture. A textbook example of seductive branding.

The Seasons (1896)

Decorative panels turned into fine art. Each figure captures nature’s mood in flowing robes and floral halos.

Le Pater (1899)

A rare spiritual project in the commercial age. Mucha’s personal masterpiece of allegorical typography and esoteric illustration.

Jewelry & Interiors for Georges Fouquet (c. 1900)

Complete artistic control, from sinuous jewelry to the architectonic boutique itself (now reconstructed at the Musée Carnavalet).

Bosnia-Herzegovina Pavilion at the 1900 Paris Exposition

Mucha designed murals, panels, and furnishings for the pavilion’s interior, blending Slavic themes with Art Nouveau. The project earned him the Austrian Order of Franz Joseph and later honors from Serbia.

Czechoslovak Banknotes & Stamps (1918)

Designing a country from scratch. These delicate motifs helped brand a new republic.

The Slav Epic (1910–1928)

20 monumental canvases, met with institutional rejection in Mucha’s time. Today, they are Czech cultural heritage.

Why He Still Matters

Mucha still matters because his work shows that visual design can be both beautiful and meaningful. Long before branding became a discipline, he gave companies a sense of poetry. Long before “design for good” entered the conversation, he embedded ethical and spiritual meaning into mass-produced images.

Even after turning his back on fame to paint forgotten Slavic legends, Mucha never stopped believing that images could uplift a nation’s soul. Though weakened by Nazi interrogation, he died under occupation, but not before completing a triptych on The Age of Reason, The Age of Wisdom, and The Age of Love. It was his final visual prayer; an artist’s quiet resistance in the face of darkness.

Home

Home Articles

Articles Twos Talks

Twos Talks Videos

Videos