Twos Studio x Centre Pompidou: The Jean-Michel Basquiat Story

From the Brooklyn graffiti scene to 1980s contemporary art, an editorial collaboration between Twos Studio and the Centre Pompidou.

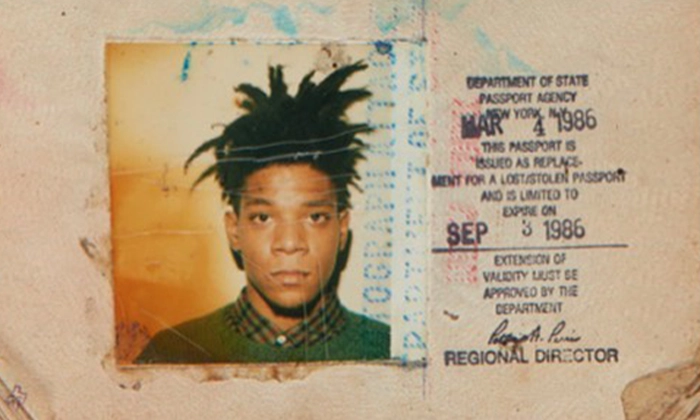

This article is based on the micro documentary video collaboration between Twos Studio and the Centre Pompidou. The documentary focuses on basquiat’s work and its movement from the streets of New York into the international contemporary art context. Jean-Michel Basquiat first appeared on the streets of New York with cryptic graffiti under the tag SAMO. Within a few years, his raw energy, bold colors, and fierce honesty placed him at the center of the art world. His time was brief, yet his influence on contemporary art has only become stronger.

Watch the official Twos Studio x Centre Pompidou micro documentary on Jean Michel Basquiat here:

Brooklyn Roots and the Birth of SAMO

Basquiat grew up in a culturally rich household in Brooklyn. His father brought home sheets of office paper that Basquiat covered in early drawings, and his mother, herself creatively inclined, took him to the Brooklyn Museum, MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By age eleven he was fluent in English, Spanish, and French, showing his Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage. A serious bicycle accident kept him in bed, during which his mother gave him Gray’s Anatomy, a book that deeply influenced his visual imagination.

In the late 1970s, while attending the alternative City-as-School in Manhattan, Basquiat became close friends with Al Diaz. Together they began spray-painting cryptic, satirical messages around Lower Manhattan under the tag SAMO (short for “same old shit”). These poetic epigrams appeared on buildings, subway trains, and other public spaces. Their graffiti often commented ironically on consumer culture, everyday life, and social norms. SAMO gained attention from the downtown art community and local media and became Basquiat’s first public voice as an artist.

From Graffiti to Canvas

Basquiat then discovered canvas and focused more on painting and less on graffiti. He looked for new ways to express his ideas and reach wider audiences. He began selling hand-painted postcards on the streets of New York for a dollar, yet just a few years later he was exhibiting in major galleries. His works carried a raw energy and urgency that contrasted with the polished gallery scene.

At just 21, he became one of the youngest artists to exhibit at Documenta in Kassel, and at 22 he was featured in the Whitney Biennial, achievements rare for someone so young.

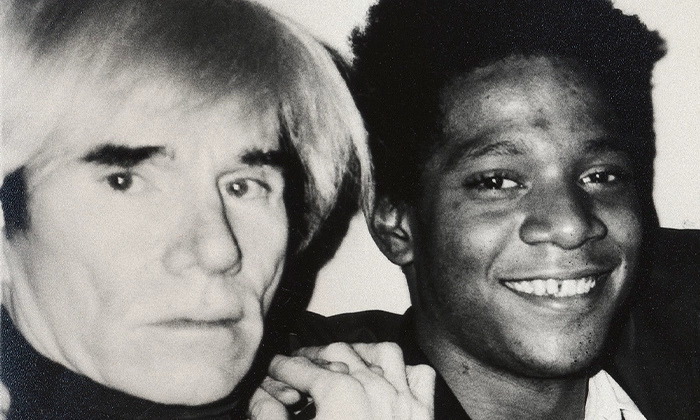

By the early 1980s, Basquiat had become the first Black artist of that decade to reach the upper levels of the contemporary art world. His work drew attention both for its visual power and the stories it told, rooted in history, culture, and personal experience, and he was seen alongside leading artists of the time, including Andy Warhol, Francesco Clemente, and Bruno Bischofberger.

Images, Words, and Symbols

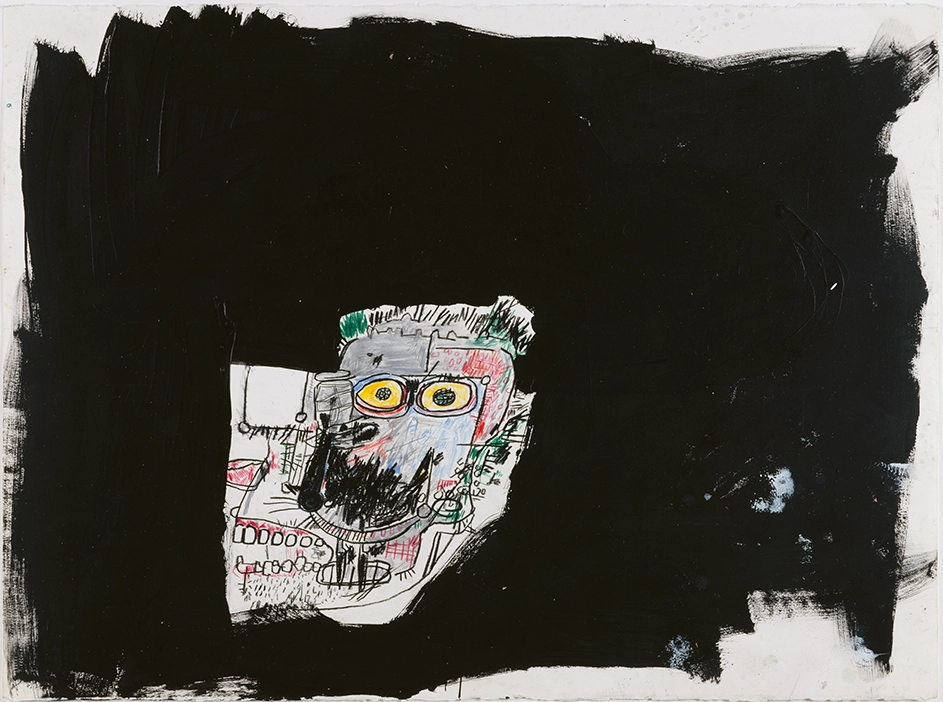

Basquiat built a vocabulary of images and symbols drawn from many sources. African art, jazz improvisation, anatomical drawings, street typography, literature, and sports heroes all entered his paintings. His background in SAMO and New York street culture is visible in his use of text, symbols, and fragmented forms.

Works such as Sans Titre (1983), now in the Centre Pompidou’s collection, show his layering of text and imagery to explore identity, memory, and cultural references. He combined these elements much like a hip-hop producer sampling music, creating paintings filled with color, symbols, and text. His skill as a colorist held this complexity together, while the three-pointed crown became a signature motif, symbolizing dignity, excellence, and visibility for himself and those he represented.

Confronting Histories Others Ignored

Basquiat’s work frequently explored stories that institutions often overlooked. His 1982 painting Slave Auction, part of the Centre Pompidou collection, combines collage, pastel, and acrylic on a large canvas. The distorted figures and skulls confront the violent legacy of slavery. Many of his works reference African heritage, colonial history, and marginalized narratives. Even at the height of his career, he remained committed to giving visibility to these histories by combining personal memory, social critique, and art history into a single voice.

Record-Breaking Art

Basquiat’s paintings have set records at auction and cemented his position in the contemporary art market. Untitled (1982) sold for $110.5 million in 2017, the highest price ever paid at auction for an American artist at the time. Other works from his peak year, 1982, have sold for tens of millions of dollars, which made him one of the most sought-after contemporary artists worldwide.

Basquiat died in 1988 at the age of twenty-seven. In the years since, his work has remained widely exhibited, collected, and discussed across museums, galleries, and cultural institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Broad in Los Angeles, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Artists, musicians, and designers still reference his approach to image, text, and subject matter.

Home

Home Articles

Articles Twos Talks

Twos Talks Videos

Videos